X Marks the Spot

The Archaeology of Piracy

Edited by Russell K. Skowronek and Charles R. Ewen

University Press of Florida

Gainesville / Tallahassee / Tampa /Boca Raton /

Pensacola / Orlando /Miami / Jacksonville / Ft. Myers

Piracy in the Indian Ocean

Mauritius and the Pirate Ship Speaker

Patrick Lizé

The so-called Golden Age of Euro-American Piracy lasted less than fifty years, from the closing decades of the seventeenth century through the 1720s. During this era the Caribbean Sea, Atlantic coast of North America, West African coast, and Indian Ocean were the main cruising grounds for pirates. This period of lawlessness came about just as the nation-states of Europe began to take on their modem borders and the trappings of centralized power - standing armies and fleets. The War of the Grand Alliance (King William's War, 1689-97) and the War of the Spanish Succession (Queen Anne's War, 1701-14) drew thousands of men into naval and privateering ships. While the central focus of these conflicts was preventing any one country from dominating the continent of Europe and upset-ting the balance of power, these were truly Worldwide wars. By the late seven-teenth century the nascent European-focused world economy was beginning to take form. In the Americas, Africa, and Asia were the colonies and trading posts of England, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. Along these long sea lanes flowed specie, spices, and slaves in the bottoms of European and local vessels. The capture of these valuable cargoes would not only enrich the lives of the victorious crew and their sponsors at home and in the government but would aid in crippling their enemy's economy and ability to wage war. These wars of empire often devolved into guerrilla warfare and piracy (Karraker 1953:29), where the adversaries would prey on enemy and neutral ships.

Part of this devolution came about because honesty cut into profits. As much as 60 percent of the value of a prize went to pay the royal share, custom duties, and court charges. One New York privateer returned to the colony in 1695 with ?160,000 in stolen goods. He paid bribes of some ?4,000 and so avoided the ?32,000 royal share and other court costs. There was indeed a fine line between privateers and pirates (Lydon 1970:48, 56-57). Nonetheless, these were the "shock troops" of imperial expansion, who would act as patriotic colonizers and

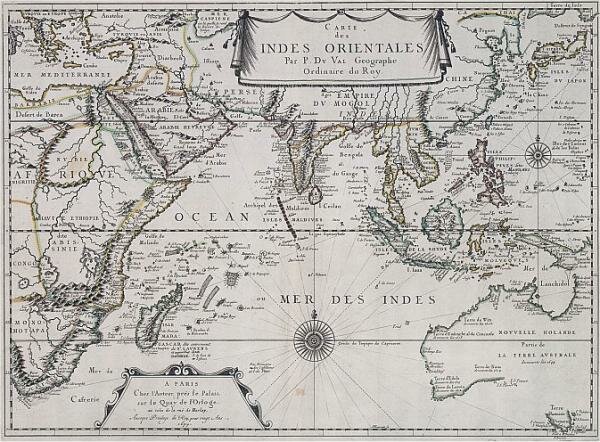

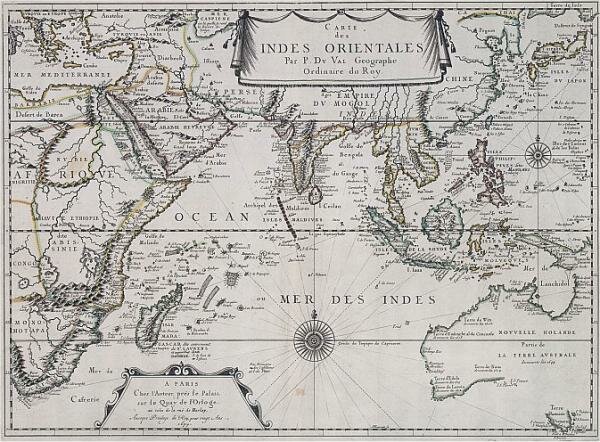

Figure 6.1. Map of the Indian Ocean, 1677. Drawn by P. Du Val (original in Biblioth?que National, Paris, GED. 15501).

Figure 6.1. Map of the Indian Ocean, 1677. Drawn by P. Du Val (original in Biblioth?que National, Paris, GED. 15501).

empire builders (Karraker 1953:55,65; Lydon 1970:58). Nowhere was this more true than in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, a remote enough locale to ensure profits while keeping Atlantic insurance rates low (Karraker 1953:66).

From its epicenter on the island of St. Mary's off the coast of Madagascar east to the Straits of Malacca and south to the Cape of Good Hope, the Indian Ocean and its adjacent seas have been termed the "Piratechnic Institute," where the majors were "Commerce and Finance" (Karraker 1953:131) (figure 6.1). These pirate colonizers were known as "The Red Sea Men" because their main cruising area was the Red Sea. This was the haunt of the likes of Thomas Tew of Rhode Island, William Kidd of New York, and John Bowen of Bermuda.

John Bowen and the Speaker

In 1702 John Bowen was in his early forties. He was described by Daniel Defoe:

We have learned from one who knew and frequently conversed with Bowen that he was born of creditable parents in the island of Bermuda who gave him a good education befitting him for the sea. The first voyage he made was to Carolina where some merchants finding him capable, sober and intelligent gave him command of a ship trading to the West Indies. He continued in this employ for several years, until he had the misfortune to be taken by a French pirate, who having no artist (sailing master) detained captain Bowen for that purpose. After cruising some time in the West Indies, the French pirates shaped a course for the Guinea coast, where he took several good artists, they would not let captain Bowen go, and not-withstanding his great services to them, treated him as roughly as they did their other English prisoners . . .

After some time cruising along the coast, the pirates doubled the Cape of Good Hope, and shaped their course for Madagascar where, being drunk and mad, they knock'd their ship on the natives Elexa; the country there-abouts was governed by a king, named Mafaly [editor's note?Mafaly is actually the name of a region in southern Madagascar. The king's name was Babaw].

When the ship struck, captain White, captain Boreman, captain Bowen and some other prisoners got to the long-boat, and with broken oars and barrel staves which they found in the bottom of the boat, paddled to Augustin Bay, that is about 14 or 15 leagues from the wreck where they landed, and were kindly received by the king of Babaw who spoke good English.

They staid here a year and a half at the king's expense, who gave them a plentiful allowance of provision, as was his custom with all White men, who met with any misfortune on his coast; his humanity not only provided for all such, but the first European vessel that came in, he always obliged them to take in the unfortunate people, let be the vessel what he would; for he had no notion of any diff?rence between pyrates and merchants.

At the expiration of the above term, a pyrate brigantine came in, aboard which the King obliged them to enter, or travel by land to some other place, which they durst not do; and of two Evils chose the least, that of going on board the pyrate vessel, which was commanded by on William Read, who receive them very civilly ...

Defoe continues:

I find him cruising on the Malabar coast in the year 1700, commanding a ship called the Speaker whose crew consisted of men of all nations, and their pyracies were committed upon ships of all nations likewise. The pyrates here met with no Manner of inconveniences in carrying on their designs, for it was made so much a trade, that the merchants of one town never scrupled the buying commodities taken from another, tho' but ten miles distant, in a publick sale, furnishing the robbers at the same time with all necessaries, even of vessels, when they had occasion to go on any expe dition, which they themselves would often advise them of.

Among the rest an English East Indian, captain Conaway from Benegal, fell into the hands of his crew, which they made prize of, near Callequilon [Quilon] ; they carry'd her in, and put her up

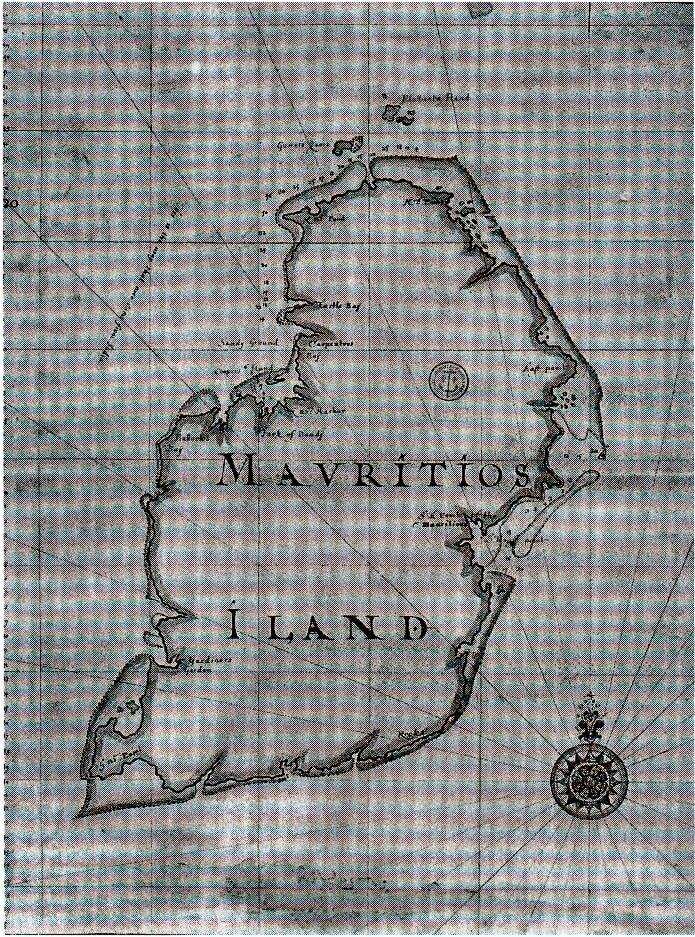

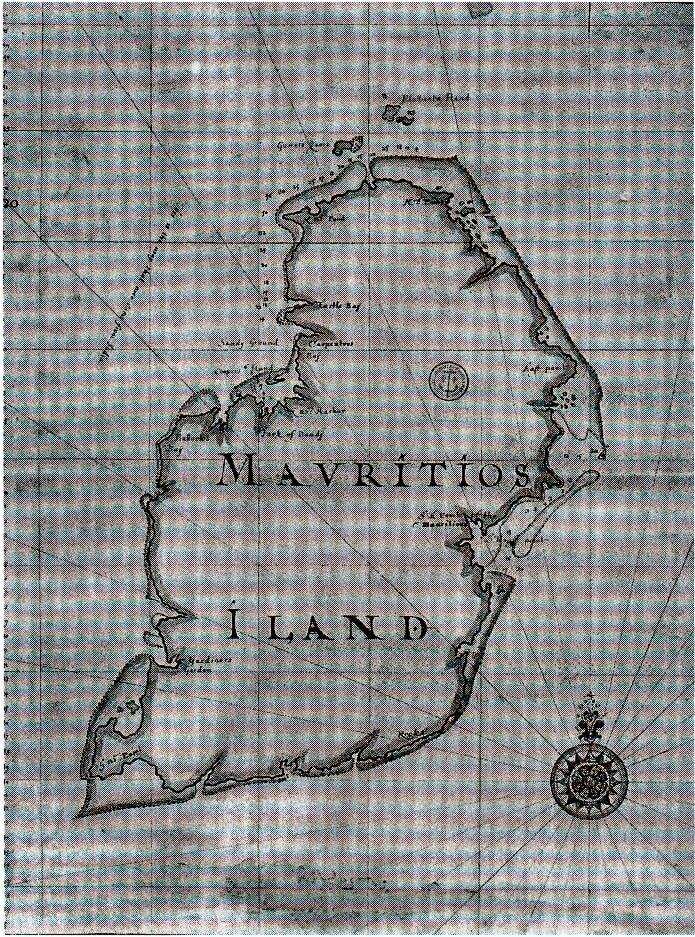

Figure 6.2 Historic map of Mauritius ? Original in Biblioth?que Nationale, Paris

to sale dividing the ship and cargo into three shares; one third was sold to a merchant, native of Callequilon aforesaid, another third to a merchant of Porca, and the other to one Malpa, a Dutch Factor.

Loaded with the spoil of this and several country ships, they left the coast and steer'd for Madagascar: but in their voyage thither, meeting with ad verse winds, and, being negligent in their steerage, they ran upon St. Thomas's reef, at the Island of Mauritius, where the ship was lost; but Bowen and the greatest part of the crew got safe ashore. (figure 6.2)

On January 7, 1702, after a violent squall, the pirate ship Speaker under the command of John Bowen sank near the "Swarte klip," now called "Ilot des Roches," off the eastern coast of Mauritius. The pirates put their boats to sea and hastily fashioned rafts, using the Speaker's masts and yards. Each was heavily armed. They all safely reached the shore (Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702a, fol. 352v; Pitot 1905:298).

On January 9 two hunters discovered them and quickly alerted the governor of the island.

They number some 170; 20 or 40 of them are Moors whose task it is to dry the weapons salvaged from the wreck. They have slaughtered three head of Company cattle, but otherwise have displayed no hostile intentions. (Alge meen Rijksarchief 1702b, fol. 366; Pitot, 1905:299)

Mauritius had belonged to the United Provinces since 1638. Then Governor Roelof Diodati, a "clever, crafty man, of dubious integrity" (Pitot 1905: 312), sent his lieutenant, Abraham Van de Velde, to determine how many pirates were actually on the island and to enter into negotiations with them.

"Should they attack us," said Diodati, while exhorting the colonists to as semble at his residence and to do their duty as honest citizens, "we shall defend the island and the fort for so long as. breath of life remains in us. For we should prefer an honorable death to the shame of begging mercy of such miscreants, from whom we may expect only the worst" (Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702a, fol. 358; Pitot 1905: 301).

Diodati had his residence fortified against eventual attack. Muskets were cleaned and loaded, pikes were sharpened, and empty bottles were transformed into hand grenades (Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702a, fol. 353v). His men were set to work repairing, reinforcing, and elevating the dilapidated defensive wall that surrounded the fort. Diodati kept a watchful eye on all this activity, inspecting the workers' progress, urging them on, bucking up the flagging morale of his troops, The tiny army of fifty colonists, two slaves, and two convicts ("some of whom knew not even how to charge a gun, loading the ball before the powder") drilled on the beach (Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702a, fol. 353v).

Upon Van de Velde's return, Diodati called a meeting of his council:

Whereas we now are certain that the pirates number 170 men (so reads the Resolution dated January 9, 1702) that they are heavily armed and could easily overrun and destroy the island; that 120 are White men; that they possess two smatl craft which take them back and forth from the wreck to shore; that among them are also 30 to 40 Lascares to Moors, who unload and polish the weapons, now spread out on the beach in great quantity; and whereas, for out part we possess only 46 muskets (most all but useless), 49 cutlasses, 4 guns and 12 cavalry pistols; our entire force consists of 52 men, including free colonists, 2 Blacks and 2 convicts, we cannot, therefore, attack the pirates and hope to overcome them. Be it then resolved, in order to prevent the pirates from ravaging the settlement and from going into the woods to forage for their food, to allow them instead to buy sweet potatoes and meat from the colonists as indeed they have requested to do; and as they cannot otherwise leave the island, it has been further resolved to sell them a small sloop, the Vliegendehart, and to permit them to bring their sick to the Residence, where our surgeon can care for them. Should we succeed in convincing a goodly number of them to enter the Residence, we have determined to fall upon them and to murder them, so that we may later lay hands on the rest and put them to death as well. (Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702b, fol. 366v and seq.; Algemeen Rijksarchief 1702a, vol. 333; Pitot 1905:299)

Bowen preferred his own barber-surgeon to the company's and was given the material he needed to enlarge the Vliegendehart, so that he and his crew could depart as quickly as possible.

On March 4, with all in readiness, the pirates took official leave of the governor, presenting him with 2,000 piastres as a token of their gratitude, They then set sail for their hideout on Madagascar.

In 1704 we find Bowen again at the helm of another captured ship, the Defi ance. Bowen pirated off the Malabar coast before retiring to Bourbon Island (Reunion Island) to live an honest life. Like many a pirate before him, he ob tained?for a price?the favor of Governor De Villers. And so, duly pardoned, he settled down and became a colonist. Bowen did not long enjoy his newfound peace. On March 13, 1705, a sudden attack of colic carried him off, before he had the time to utter a single word.

No pomp marked his funeral. A simple grave dug in the underbrush was Bowen's final resting place. The colony's priest, Father Marquer, refused to bury Bowen, a heretic, in consecrated ground. Bowen left no heirs; he bequeathed to the company a 14-year-old slave. Nonetheless, he was one pirate who died wealthy; and that wealth did not go unnoticed, as the court clerk wrote down:

After having sealed his sea-chest at 10 o'clock in the morning, in the pres ence of several colonists, said box was later opened, and an inventory made of its contents:

- In gold, 750 Moorish and Arabian sequins, worth 1,500 ecus, or 2 ecus each.

- Old and used clothing, such as jerkins, shirts, caps, which was divided among those who had aided him in his illness, and those who had helped to bury him. (C2 Col, Item 11, Archives Nationales, Paris)

The Speaker

Contemporary sources described the Speaker as a former French warship captured by the English during the War of the League of Augsburg (Ring William's War). Unfortunately, its former name is unknown. Pirates are not renowned for keeping written records, and Bowen was no exception. Nonetheless, their victims left behind documents, which have allowed us to trace the Speaker's itinerary and to know its size and the prizes it took.

In his deposition dated November 2, 1702, Thomas Towsey, who was held for six months and obliged to serve as a carpenter on the Speaker, says that the pirates robbed two Moorish ships belonging to Surat and one Dutch ship, the Borneo, a 300-ton vessel bound from Bengal to Surat.

We learn from Ashin Das Gupta (1979:101):

On the 23 Sept. 1701, news reached Surat that Abdul Gafur's ship the "Hussaini" had been plundered by pirates off Daman and the Dutch cruis-ers escorting the Red Sea fleet, of which the "Hussaini" was one, had done nothing . . . Besides the "Hussaini," two other ships were missing. One of them, a vessel of Gafur's friend Mia Muhammad, turned up shortly after, thoroughly plundered, while the third, another of Gafur's remained missing.

Other documents give us information about the Speaker's size. The Resolution of the Island Council of Mauritius, dated September 1, 1702 (Algemeen Rijk-sarchief 1702a, fol. 353v), tells us that the ship measured around 145 feet and carried 40 cannon. According to Conaway, the Speaker was a ship of 500 tons, mounting 40 guns and two patereroes (E-3-70 No. 8592; Hill 1919:32).

Finally, the documents left by the Island Council indicate that the Speaker sank near the Swarte Klip.

Discovering the Speaker

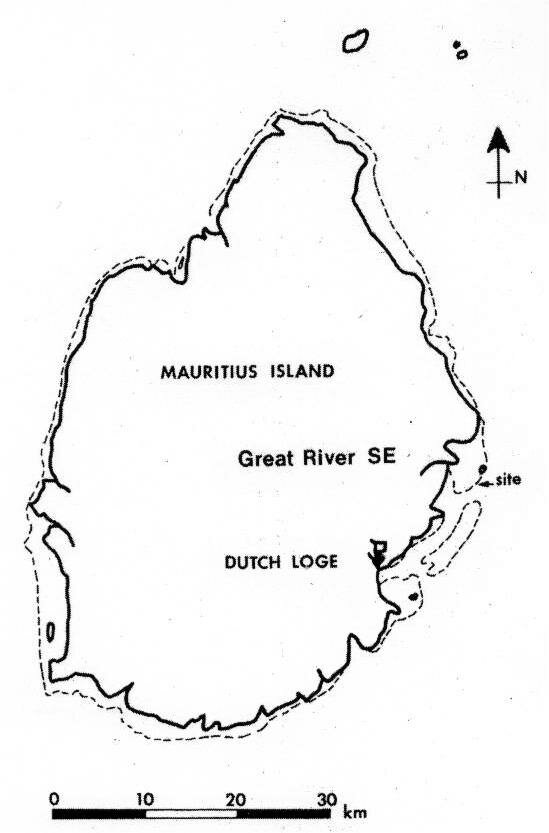

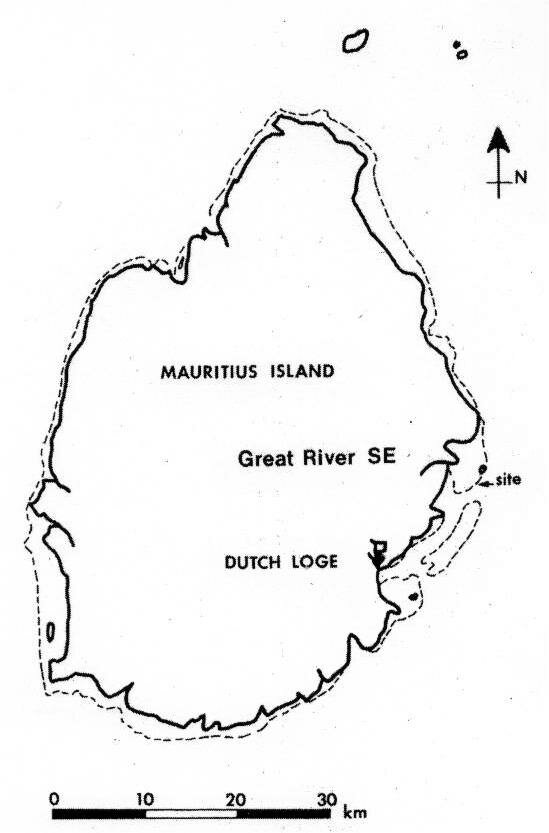

The island of Mauritius (61 km long and 47 km wide) is situated in the Indian Ocean about 1,083 km east of Madagascar (figure 6.3). Discovered by the Por-tuguese in 1511, the island remained uninhabited until 1638, when the Dutch colonized it as a base to refresh their ships traveling to or from the East Indies.

In July 1980 a French research team, in coordination with the National Com mission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), signed a draft treaty with the Mauritian government to investigate the wreck site. The site was investigated from September to December of the same year. Prior to the field aspect of the project, archival research relating to the loss of the Speaker was undertaken by M. J. Dumas and myself.

The wreck of the Speaker is located 1 km south of a small Rocky Island (Ilot des Roches), and some 2 km offshore from Grand-Rivi?re southeast (figure 6.3). The reef where the Speaker lies is covered with less than 5 meters of water and is exposed to heavy southeasterly swells. Periods when diving is possible occur from October to December and in March, unless, of course, unforeseen cyclones occur. As a resuit of these conditions the wreck is dispersed, poorly preserved, and especially hard to work. None of its timber structure survives. Instead, ail that remains is a large debris-field covering some 5,000 square meters of reef, consisting of durable artifacts encased in coral. The debris occurs in two main areas: around cannon number 30, where we found silver coins, a padlock, beads, lead ingots, a grindstone, rings, dividers, and a sundial; and around cannon number 7, where we found gold coins and gold bars.

The site (figure 6.4) occupies an area about 100 by 50 meters and is practically perpendicular to the reef. It is covered by a growth of coral that is fairly stunted, due to perpetual battering by the sea. A sandbank, edged on its northeast side by a bed of sea-plants, divides the site into two unequal areas.

Figure 6.3. Map of Mauritius, locating the Speaker site.

The Artifact Assemblage

Figure 6.3. Map of Mauritius, locating the Speaker site.

The Artifact Assemblage

During the project the following artifacts were collected or noted.

Artillery

Thirty-one cannon measuring from 1.2 m to 2.5 m lay on the seabed.

One of them is unfinished and was probably used for ballast.

Ammunition

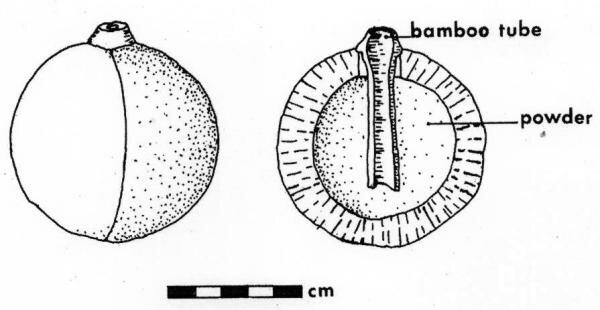

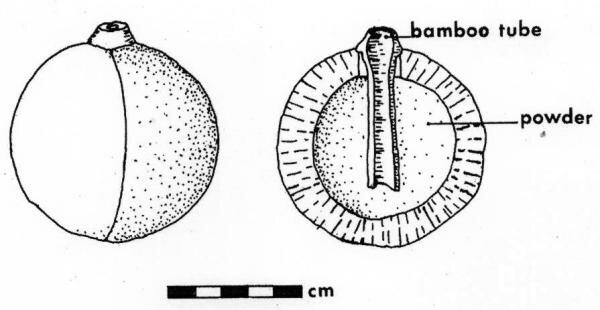

Figure 6.6. Hand grenade.

Figure 6.6. Hand grenade.

Ordinary lead musket balls were recovered in large quantities all over the site, as were many cannonballs of different sizes and hand grenades. The hand grenades found on the wreck (figure 6.6) are hollow cannonballs filled with black powder and pierced with a circular hold in which a bamboo tube was inserted to serve as a conduit for the fuse (description in Saint-R?my 1702:1:305-13; 2:373). Similar grenades have been found in the Evstafii (Stenuit 1974:221-43) and the Whydah (Kinkor 1991; Clifford and Perry 1999b:223).

Navigational instruments

Figure 6.7. Brass navigation dividers.

Figure 6.7. Brass navigation dividers.

Five pairs of brass navigation dividers in extremely fine condition were found (figure 6.7) They are of a classical type that can be opened and closed with one hand. Similar examples h?ve been recovered from the Lastdrager (Stenuit 1974) and Kennemertand (Price and Muckelroy 1974).

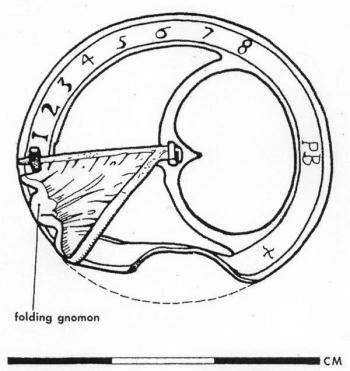

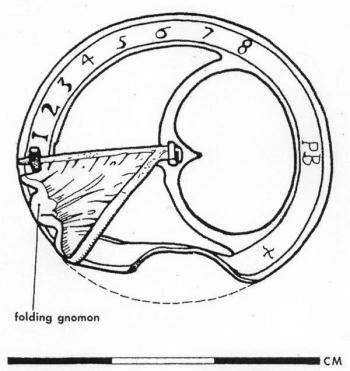

Part of a compass dial (figures 6.8 and 6.9) was found. It consists of a graded brass disc with a folding gnomon. The complete instrument would be a canister or cylindrical bowl fitted at the upper part with this disc and at the bottom with a compass rose and magnetic needle protected by glass. The instrument found in the Speaker is a typical sundial from Nuremberg (Guye and Fribourg, 1970:fig-ure 249). The container was usuaily made of wood, ivory, or gilded brass. The initiais "PB" are probably those of the maker. Some very similar examples were found on the Lastdrager and Kennemerland (Price and Muckelroy 1974; Stenuit 1974).

Figure 6.8. Illustration of a compass dial.

Figure 6.8. Illustration of a compass dial.

Figure 6.9. Brass compass dial.

Figure 6.9. Brass compass dial.

Figure 6.10. Tobacco pipe fragments.

Figure 6.10. Tobacco pipe fragments.

The wreck held a large number of clay tobacco pipes bearing no mark (figure 6.10).

Padlock

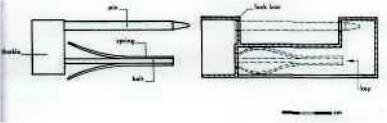

Figure 6.11. Brass padlock

Figure 6.11. Brass padlock

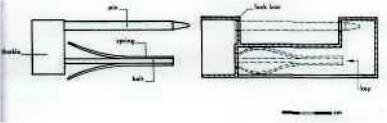

Figure 6.12. Illustration of brass padlock.

Figure 6.12. Illustration of brass padlock.

A brass padlock 10 cm long was round on the wreck (figure 6.11). It is the Chinese type of lock (Eras 1974:43-45). The pin that goes through the two ears of the padlock is of a single piece, with the shackle and a bolt that bears thc plate springs (figure 6.12). By simply pushing the shackle into the lock box, the springs are expanded, the spring-terminals are caught by two flanges, and the lock is thus secured. To open it the key must be slid into the box until it presses the springs

Figure 6.13. Beads from the Speaker.

Beads

Figure 6.13. Beads from the Speaker.

Beads

A cache of trading beads was discovered on board the Speaker (figures 6.13) and 6.14). They are garnets, agates, and glass beads, which even today are referred to as rassade. (because of their brilliance) or contrebrode (bccause of their resemblance to a black and white embroidered fabric).

Rassade beads are large glass rosary beads of different colors and sizes. "They are of coarse glass. They are manufactured in large quantities in Venice. A white or black background is decorated with lines of different colors; a design that made the beads look as if they had been embroidered.Negroes use them to make belts composed of several string of the beads, which young men wear around their hips, in lieu of clothing until they reach a certain age" (Labat 1730:28).

Trade in in these beads was considerable in the eighteenth century. In 1725 the Chevalier Des Marais brought no less than two thousand pounds of them into Guinea (ibid.)

The "samsam" variety is a large dark red agate striated with white, with a hole bored through, so it can be worn as a pendant (Lougnon 1956:111). The ex amples found on the Speaker are of two types. The first sort are spherical, 10 mm in diameter; the otlhers are elongated, faceted bead from 20 to 30 mm long.

Statues

Two bronze statues were discovered close to anchors A and B but were too eroded to be identified with precision (figure 6.15). Still, one can say with cer tainty that they come from the south of India. One of them is distinguished by an undulating pose that brings to mind a dancer. The other, perfectiy erect, seems to represent a divinity.

Figure 6.15. Bronze statue from south India.

Figure 6.15. Bronze statue from south India.

Gold ingots

Gold ingots

Two small gold ingots bearing no marks, were found at the site (150g and 100g). On both of them it is possible to make out the traces of the sand from from the mold in which it was cast as well as the mark of a chisel blow, which indicates that they were split.

1a, 1b Gold coins of the Ottoman empire, minted during the reign of Mohammed IV (1648-87).

1a, 1b Gold coins of the Ottoman empire, minted during the reign of Mohammed IV (1648-87).

2a, 2b Gold Venetian ducats minted under Francisco Morosini, 108th doge of Venice (1688-94).

Below is a list of coins found at the site :

1. A gold coin of dinar of the Ottoman empire, minted in Cairo in the year 1053 of the Hegira (AD 1643-44) during the reign of Ibrahim (AD 1640-48) (figure 6.16) (British Museum Catalogue III : 131 n? 358 ; Pere 1968 : n?429)

2. A gold coin of dinar of the Ottoman empire, probably minted in Egypt during the reign of Mustapha I [also spelled Mustafa]. The coin is incompleted and double struck on both sides, the flan having turned over between the dies during the minting process. Neither the mint nor the date can be read.

3. A gold coin of dinar of the Ottoman empire, minted in Cairo under the first reign of Mustapha I (1617-18) (figure 6.17) (British Museum Catalogue VIII:115 ; Pere 1968 : n?378)

4. A gold coin of dinar of the Ottoman empire, probably minted in the year 1065 of the Hegira (AD 1654-55) under Mohammed IV, son of Ibrahim, who ruled 1648-87 (figure 6.18)

5. Two Venitians ducats of gold, minted under Francisco Morosini, 108th doge of Venice, whose reign lasted from 1688 to 1694 (figure 6.19) (Corpus Nummorum Italicorum, VIII, pl.19, n?5, 94-99)

6. A silver taler, struck in Kremnitz in 1695 during the reign of Leopold of Austria (Corpus Nummorum Austriacorum, 1975, n?86, a-7)

7. A silver coin from the Netherlands struck in the Dordrecht mint in 1602 (Delmonte 1967 : n? 831)

8. Four real pieces, minted in Mexico, badly worn.

9. Two Spanish eight-real coins, minted in Mexico, badly damaged (figure 6.20)

10. A silver rupee from India (mounted as a pendant) minced in the work-shop of Itawa (or Etawa) in the year 1102 of the Hegira (1658-1707)

11. Silver coin of Zaydi Imams, of the reign of al-Mahdi Muhammad b. Ahmad, "Sahib al-Mawahib" (1687-1718), with the title "al Nasir li-Din Allah," minted at al-Khadra, date miissing (Lowick 1983: 307n31).

12. Silver coin of the same Imam, but with the title "al-Hadi li-Din Allah", minted in 1697

13. Two silver coins of the Ottoman Empire, minted at Cairo under Sulayman II (1687-91), date missing.

14. Silver coin of Nayaks of Tinnevelly, sixteenth century or late (observe : divinity standing under an arch ; reverse : Tamil inscription)

Identifying theWreck

The positive identification of the ship whose scattered remains heve been found was made possible throush the study of officiel records. As discussed above, the documcntary evidence comes from the legal depositions of some of the Speaker's victims. For example, the carpenter Thomas Towsey said that several ships of different cultural origin had been plundered by pirates. These numerous seizures, which seem to be the work of Bowen and his crew, might explain the diversity of the coins found at the site.

Other documents give us information about the Speaker's size, an important element in identifying a ship. Those accounts say that the Speaker was a 500-ton ship armed with forty guns. During the project, thirty-three guns and three anchors of a size appropriate for use on a 500-ton ship were located. Finally, the Island Countil indicates that the Speaker sank near the Swarte Klip, in the very area where the wreck was found.

All these factors, the lack of any other recorded shipwreck in this region, and especially the coins (which are all pre-1702) permit us to assume that the ship we found is indeed the Speaker.

Conclusion

The Speaker is of great historical and archaeological value as the first pirate ship to be investigated archaeologically. Had it not been for the documentary evidence relating to Bowen and the Speaker, nothing discovered on this wreck site would have told researchers that it was the remains of a pirate ship. Nonetheless, this salvage operation has allowed us to write a new page in the history of Mauritius.

Acknowledgments

At this end of this ptoject, I have the honor and the pleasure of thanking those who participated in it - Jacques Dumas, Pascal Kainic, J.F Leitncr, and Yves Halbwacks?and all those who gave us their material help or moral support. Let me mention first of all G?rard Delaplace; Mrs. and M. De Heuriot; Sir Raymond Hein; Mike Seeyave; Michel Camus; the Mauritian governmemt, of course, especially the Ministry of National Education and Cultural Affairs; S. E. Kher Jagat-singh; David Ardill; the UNESCO Commission, particularly B. R. Goordyal, A. Murday, and G Sooknah and Mr Tirvergadum director of the Mauritius Institute. Many thanks go as well to the experts and specialists who assisted us with the identifications : Mr Curiel, Mr. Dhenin of the cabinet or Medals of the Biblioth?que Nationale of Paris Mr Lowich of the Cabinet of Coins and Medals of thc British Museum, London, Mr Haudrere ot the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Mr hutchinson, curator of the Departmem of Navigation and AStronomy, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, Mr. Poirot from the Laboratory of the Diamond Exchange in Paris; Mrs. Prade, of the Museum Bricard in Paris, and Mr Henrat, curator of the Archives Nationales in Paris. Many thanks to my colleagues in Portugal at the Centra Nacional de Arqueologia Nautica e Subaquatica for teir ongoing support. Finally I wish to thank Nelly Mesclef for her help and also Charles Ewen of East Carolina University as well as Russell Skowronek, Demetra Kalogrides, Jessica Crewse, and El-wood Mills of Santa Clara University for their edirorial review of this chapter. The translation is by Sheila Mooney-Mall, and the figures are by Patrick Liz? unless otherwise noted.