Correspondence in Clay

�

Written by Barbara Ross

"I am going to have a house-warming," read the invitation. "Come yourself to eat and drink with me. Twenty-five women and 25 men shall be in attendance." The party favor promised was "10 wooden chariots and 10 teams of horses"?a lavish gift by ordinary standards, but this invitation was from royalty. It was sent some 3500 years ago by Kadasman-Enlil, king of Babylonia, to Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), pharaoh of Egypt. The message was inscribed on a pillow-shaped clay tablet, small enough to be carried easily in one hand or slipped into a satchel.

"I am going to have a house-warming," read the invitation. "Come yourself to eat and drink with me. Twenty-five women and 25 men shall be in attendance." The party favor promised was "10 wooden chariots and 10 teams of horses"?a lavish gift by ordinary standards, but this invitation was from royalty. It was sent some 3500 years ago by Kadasman-Enlil, king of Babylonia, to Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), pharaoh of Egypt. The message was inscribed on a pillow-shaped clay tablet, small enough to be carried easily in one hand or slipped into a satchel.

The letter was one of hundreds uncovered in the late 1800's, when a peasant woman rummaging through the ruins of Akhetaten, an ancient city near modern-day Tell El-Amarna, came across a cache of small clay tablets covered with unfamiliar script. She took several to a merchant, who immediately purchased them. Word of the tablets spread quickly, and in a short time the site was buzzing with local residents, each hoping to find something of marketable value. The hoard was excavated, and most pieces were sold to the highest bidders. Today there are about 380 significant texts scattered among private collectors, antique dealers and museums, mostly in Egypt and Europe, and collectively these clay-tablet texts are known as the Amarna Letters.

The letters, which cover approximately three decades, hold a particular fascination because their place in Egyptian history is unique. They begin late in the reign of Amenhotep�III and end during the first year of the reign of Tutankhamen; in between they cover the entire 17-year reign of Akhenaten, whose rule between 1353 and 1336�BC was perhaps the most dynamic and far-reaching in its effects of any reign in any of the 30 or so Egyptian dynasties that ruled over the course of 3000 years. Often referred to as the "heretic king," Akhenaten was the first Egyptian king to worship a single deity. (See Aramco World , September/October 1994.) He forbade the worship of multiple gods, and he directed an entire society to worship one supreme being represented by the sun, which he referred to as "Aten." With his wife, Nefertiti, and their young daughters, the royal family moved from Thebes, the capital of Egypt, to a palatial city he had built along the east bank of the Nile some 300 kilometers (185 mi) to the north. He named his city Akhetaten ("Horizon of Aten"), and today it is known as Amarna.

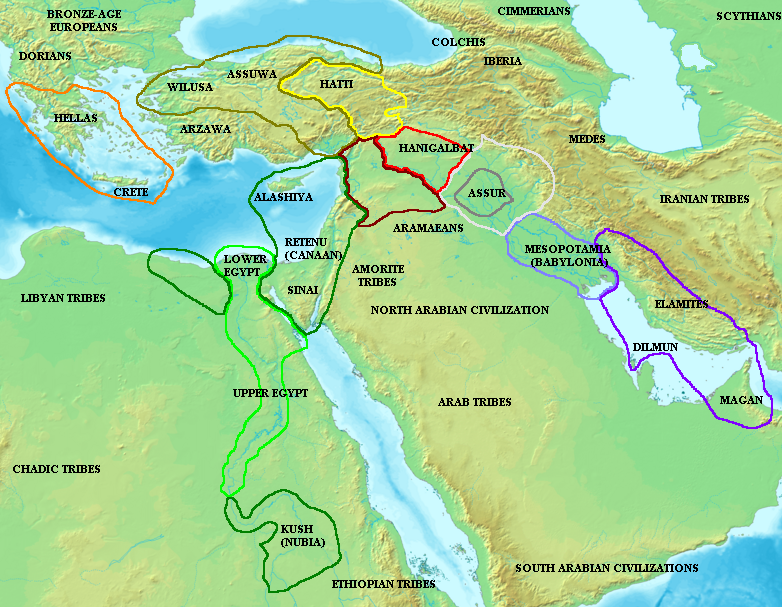

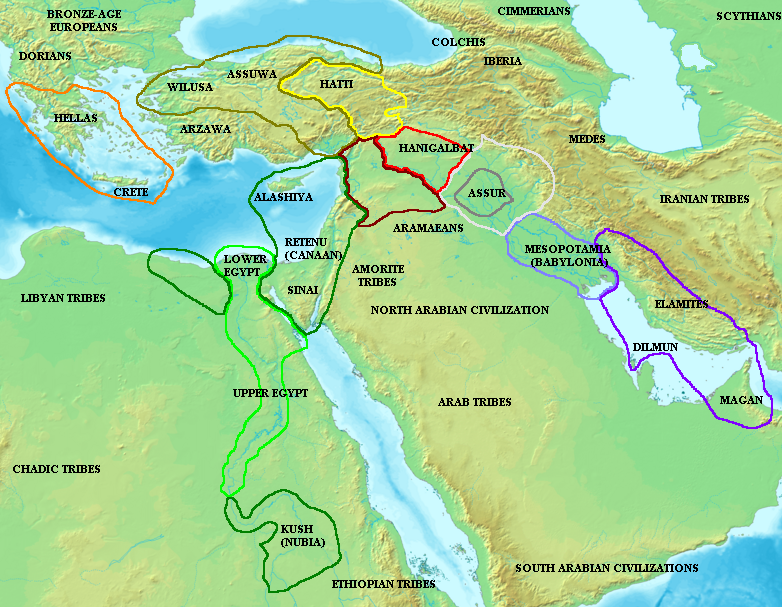

Politically, Egypt was at its zenith, the most powerful kingdom the world had known, dominating the lesser empires of Babylonia, Assyria, Khatti, Mitanni and Alashiya (Cyprus), and the provinces of Syria, Palestine, Canaan and Kush. The Amarna Letters were diplomatic correspondence between the pharaoh and the rulers of these lands, or the vassals who governed towns and cities under Egyptian control.

Map of the ancient Near East during the Amarna period, showing the great powers of the period: Egypt (green), Hatti (yellow), the Kassite kingdom of Babylon (purple), Assyria (grey), and Mittani (red). Lighter areas show direct control, darker areas represent spheres of influence. The extent of the Achaean/Mycenaean civilization is shown in orange.

Each letter observed a protocol, and in doing so it eloquently expressed the relationship of the sender with the Egyptian court?generally, in fact, with the pharaoh himself. John Huehnergard, professor of Near Eastern language and civilization at Harvard University, explains that the language of brotherhood and love so common in the letters "is meant sincerely, because it was also code for diplomatic relations. 'Brothers' were allies, and to 'love' one's brother was to be in a treaty relationship with the other king."

After a flurry of courteous salutations, most letters included a plea for money, gifts or military troops. This is a typical introduction: "Say to Nimmureya [Akhenaten], the king of Egypt, my brother, my son-in-law, whom I love and who loves me: Thus Tushratta, the king of Mitanni, your father-in-law, who loves you, your brother. For me all goes well. For you may all go well. For your household, for your wives, for your sons, for your magnates, for your chariots, for your horses, for your warriors, for your country and whatever else belongs to you, may all go very, very well."

The meat of the letter would quickly follow. In this case, Tushratta announced that he was sending one of his mistresses as a gift to the pharaoh. "She has become very mature, and she has been fashioned according to my brother's [Akhenaten's] desire. And, furthermore, my brother will note that the greeting gift that I shall present is greater than any before."

The letters were dispatched by messengers who were members of each monarch's council. When these emissaries were required to travel through unwelcoming territories, where they risked thieves, thugs and political enemies, their job was difficult?but so it might be once they arrived, too: Occasionally a messenger from abroad would be held by the pharaoh himself. In another letter, Tushratta complains of this problem:

"Previously, my father would send a messenger to you, and you would not detain him for long. You quickly sent him off, and you would also send here to my father a beautiful greeting-gift. But now when I sent a messenger to you, you have detained him for six years, and you have sent me as my greeting-gift, the only thing in six years, 30 minas of gold that looked like silver."

This testy passage is startling considering that Akhenaten was the richest and most powerful man in the world, for it implies that the Mitanni king was offended by a gift of what he suspected was counterfeit or debased gold. However, Tushratta and his father had maintained an unusually close relationship with Akhenaten's father and grandfather. The Mitanni, in western Mesopotamia, were among Egypt's most important allies, and several princesses had been sent as brides to marry Akhenaten and his father, Amenhotep III. A kinship evolved between the rulers that elevated Tushratta above the role of a mere ally, and the terms of endearment in the letters to him were probably more than matters of protocol.

The written word of the time was cuneiform, a type of writing that had spread from Mesopotamia beginning in the third millennium BC, and was used to write several languages at different times and places. The Amarna Letters are mostly written in Old Babylonian, itself a dialect of Akkadian, a spoken and written language that developed in the city of Akkad, now in Iraq. At the time the letters were written, Old Babylonian had become infused with West Semitic and Egyptian words, and it had become the common regional language that unified international relations and trade, a lingua franca.

Because written tablets often carried political and commercial communications, their production was important business, and from the evidence in scenes etched on tomb walls, the scribes who wrote them enjoyed high status. Each country outside Assyria and Babylon, where Akkadian was the first language, had to maintain a staff of trusted, educated people who could interpret and write in Akkadian. For example, when the Egyptian king dictated a letter, his scribe probably wrote on papyrus. The scribe would then hand his text to a translator, who would inscribe it into clay in Akkadian. The tablet would then be dispatched by royal courier. If it was addressed, for example, to the Hittite king, the courier would have to gain admittance to that king's palace and hand the tablets to the Hittite king's interpreter, who would in turn translate the message into Hittite for presentation to his king.

This was an era in which diplomacy was often urgent, for throughout the Amarna period many of Egypt's vassals were at war with each other. Some letters discredited the sender's enemy in terse terms, as in this letter from Rib-Hadda, king of Byblos:

"Who is 'Abdi-Asirta, the servant and dog, that they mention his name in the presence of the king, my lord? Just let there be one man whose heart is one with my heart, and I would drive 'Abdi-Asirta from the land of Amurru."

In the same letter, Rib-Hadda eloquently pleaded for help: "Since he has attacked me three times this year, and for two years I have been repeatedly robbed of my grain, we have no grain to eat. What can I say to my peasantry? Their sons, their daughters, the furnishings of their houses are gone, since they have been sold in the land of Yarimuta for provisions to keep us alive. May the king, my lord, heed the words of his loyal servant and may he send grain in ships in order to keep his servant and his city alive."

In another letter, Rib-Hadda thanked the pharaoh for requesting help for him: "Moreover, it was a gracious deed of the king, my lord, that the king wrote to the king of Beirut, to the king of Sidon, and to the king of Tyre, saying, 'Rib-Hadda will be writing to you for an auxiliary force, and all of you are to go.' This pleased me, and so I sent my messenger, but they have not come, they have not sent the messengers to greet us."

Apparently, the troops never arrived. Although Rib-Hadda was a close ally and had dispatched numerous letters petitioning for help, Akhenaten did not go any further to assure his protection. As a result, Byblos was sacked, and the king was taken prisoner and put to death.

Scholars of the Amarna tablets wonder why Akhenaten did not respond more effectively to Rib-Hadda, but it was almost certainly a political calculation. "The Egyptian king had to balance his troop commitments," says Huehnergard. "He had troops deployed in the south [Nubia], west [Libya], and in garrisons in his Syro-Palestinian territories. To go to the aid of Rib-Hadda would have required a much larger force with the sole purpose of maintaining the status quo balance of minor powers in the region. The king opted instead to let the expansion of Amurru run its course, to poor Rib-Hadda's detriment."

In a tumultuous political sea, what remained fixed throughout Akhenaten's reign was his ardent adoration of Aten. Amarna was built with roofless courtyards, temples, and shrines to facilitate worship directly toward the sun?although shade was provided for the royal family. An Assyrian king protested to the pharaoh on behalf of his emissaries:

"Why are my messengers kept standing in the open sun? They will die in the open sun. If it does the king good to stand in the open sun, then let the king stand there and die in the open sun. Then will there be profit for the king! But really, why should [my messengers] die in the open sun?"

Although many letters contain similarly heated protests of the pharaoh's ways, he appears to have remained largely unmoved, for his power dwarfed that of other empires. Tushratta, the king of Mitanni who was offended by a questionable gift from the pharaoh, plainly conceded, "In Egypt, gold is more plentiful than dirt." In the same letter, he elaborated on why he and his friends were not impressed with the gift of gold recently sent to him:

"And with regard to the gold that my brother sent. I gathered together all my foreign guests. My brother, before all of them, the gold that he sent has been cut open.... And they wept very much saying, 'Are all of these gold? They do not look like gold.'"

Akhenaten may have incurred the ire of his vassals abroad, much as other great powers have throughout history, but there is evidence that he was a devoted husband and father. He and Nefertiti had at least six daughters, and reliefs found on shrines, temple walls, and burial sites show hints of intimacy and domestic contentment that are unique in pharaonic art. In one painting, the king and queen are seated under a sun-disc whose rays end in tiny hands, which symbolize the life-giving force of the sun. Their three eldest daughters, Meritaten, Meketaten, and Ankhesenpaaten, are often depicted in scenes that display an unusual degree of affection between them and their father.

Akhenaten died after 17 years of reign and was succeeded by Smenkhare, who had married Meritaten. Smenkhare ruled for four years, and was himself succeeded by Tutankhamen, who may have been either Akhenaten's younger brother, or Akhenaten's son by a minor queen. The nine-year-old pharaoh married Akhenaten's youngest daughter, Ankhesenpaaten, and ruled until his untimely death nine years later. This left his wife a widow while she was still, presumably, only in her teens.

During Tutankhamen's reign the capital was moved back to Thebes, and the old polytheism was reinstated. It is widely believed that the young king Tutankhamen was manipulated by older, craftier advisors who saw a return to past ways as a means of restoring their own power. One of the closest advisors to the king was a nobleman named Ay, who had been a faithful follower of Akhenaten.

But after the political climate changed following Akahenaten's death, he had became sympathetic to the Theban priests who still prayed to the ancient Egyptian pantheon. In the absence of a male heir to Tutankhamen's throne, Ay became the designated candidate?but the prerequisite of his ascent was marriage to Tutankhamen's young widow, who was at least 30 years his junior.

To take Ay as her husband would have been ignominious for Ankhesenpaaten, and her desperate search for a suitor who might supplant him bespeaks a feisty and determined temperament. She scoured her own realm unsuccessfully and finally resorted to an unprecedented search beyond Egypt. That step produced one of the most famous and touching letters of the Amarna Period, authored by the distressed young woman. One of the only ones known to have been dispatched from Egypt rather than received there, it was discovered in the ancient city of Hattusas (modern-day Boğazk?y in central Turkey), seat of the Hittite king Suppiluliumash. "My husband has died," she wrote, "and I have no son. They say about you that you have many sons. You might give me one�of your sons, and he might become my husband. I would not want to take one of my servants. I am loath to make him my husband."

It was earth-shattering for a woman of her stature, queen of a great empire, to request such a thing from one of Egypt's vassals, but the reference to her betrothed as a servant gave proof of her distaste for Ay. King Suppiluliumash must have been stunned; yet he quickly took advantage of the opportunity and dispatched one of his princes. But the young man was murdered on his way to Egypt, and so Ankhesenpaaten did in fact marry Ay.

Ay reigned for four or five years, and he is believed to have continued the Theban building projects at Karnak and Medinet Habu. Ankhesenpaaten fades from the record, but a blue glass ring, inscribed with both her name and Ay's, was found in the ruins at Amarna. Ay was succeeded by Horemheb, who detested Akhenaten's monotheism and dispatched men to obliterate everything Akhenaten had created. What survives today of Akhenaten's legacy is but a small part of what once existed, and Horemheb's destruction is part of the reason that the reign of Akhenaten sank into obscurity until its rediscovery in the early 19th century. As for the Amarna Letters, although the form of communication doubtless continued, there have been no corresponding caches of correspondence found in Thebes, and thus the record ends approximately a year after the capital was moved back there from Amarna, during the reign of Tutankhamen.

The legacy of the Amarna Period is great. While some scholars credit Akhenaten with the inspiration for monotheism, more agree that his patronage of artistic realism left an even clearer legacy. In the vaulted halls of the Cairo Museum, silhouette statues of the "heretic king" are distinctly unlike those of prior pharaohs, who appear with broad shoulders, perfectly shaped features and robust physiques. Akhenaten chose a different iconography: he was depicted with narrow shoulders, a bulbous belly and swollen breasts. Whether or not this interpretation was Akhenaten's own choice, or merely the artists' realistic representation of the king's physique, has puzzled scholars ever since Amarna was uncovered.

Yet beyond scholarly questions, what makes the Amarna period riveting is the poignancy of the letters and the personal faces they present. Through them, we can clearly envision the indignant Assyrian king fuming over the treatment of his emissaries, the ill-fated Rib-Hadda pleading for relief, and the desperate royal widow embracing a lesser humiliation to avoid a greater one. The Amarna Letters are our only intimate glimpses into lives lived in a world so distant from our own in time, yet so similar in its humanity.

�

Free-lance writer Barbara Ross travels frequently to the Middle East and writes often on Egypt. She lives in Boston.

�

This article appeared on pages 30-35 of the November/December 1999 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

"I am going to have a house-warming," read the invitation. "Come yourself to eat and drink with me. Twenty-five women and 25 men shall be in attendance." The party favor promised was "10 wooden chariots and 10 teams of horses"?a lavish gift by ordinary standards, but this invitation was from royalty. It was sent some 3500 years ago by Kadasman-Enlil, king of Babylonia, to Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), pharaoh of Egypt. The message was inscribed on a pillow-shaped clay tablet, small enough to be carried easily in one hand or slipped into a satchel.

"I am going to have a house-warming," read the invitation. "Come yourself to eat and drink with me. Twenty-five women and 25 men shall be in attendance." The party favor promised was "10 wooden chariots and 10 teams of horses"?a lavish gift by ordinary standards, but this invitation was from royalty. It was sent some 3500 years ago by Kadasman-Enlil, king of Babylonia, to Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV), pharaoh of Egypt. The message was inscribed on a pillow-shaped clay tablet, small enough to be carried easily in one hand or slipped into a satchel.